I'm excited to release more information about a paper I wrote titled A Five Axis Robotic Motion Controller for Designers which was selected for publication and presentation for this year's ACADIA 2011 Conference: Integration Through Computation held in Banff, Canada from October 13th-16th. Click here to download the full paper.

This project aims to bring physical input and output closer together through the design purpose-built tools for fabrication, which hopefully leads to many new creative opportunities for designers. Working from observations about the way architects design, this project explores the development of a novel 3D drawing tool or customized 5-axis digitizing arm that takes real-time input and translates movement patterns directly into machine code for robotic fabrication. An improved workflow for robotic simulation was also developed as part of this project; using design tools that are already familiar to architects and designers, such as Rhino and Grasshopper. The purpose of this project was not to suggest that this new workflow is a ready-made solution to replace the existing robotic fabrication process; rather I hope that this work is seen as a proof of concept that could enable wider use of digital fabrication tools by architects and designers.

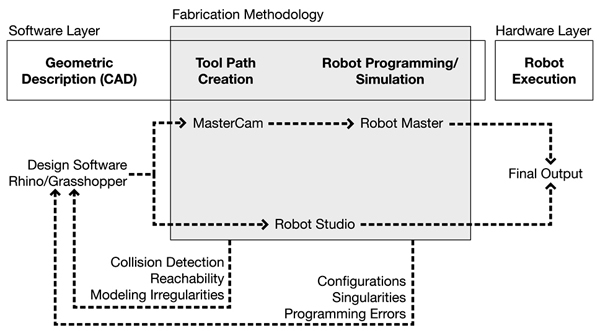

The existing design-to-fabrication workflow for industrial robots (seen above) has traditionally been a slow and cumber-some process, especially for designers. Machine tooling, kinematic simulations, and robotic movement programming often require intimate knowledge of scripting and manufacturing processes, all of which limit the utilization of such tools by the 'typical' architect/designer.

In the traditional robotic fabrication workflow, there is often a discrepancy between the original design intent and the final output, primarily because there is an intermediate step where the designer has to hand off a digital model to a fabrication consultant who has more intimate knowledge of the specific robotic CAM software and the fabrication process in general. Typically, this consultant will use programs such as Robot Studio or Master CAM to create the necessary tool paths for the design, however this process can often take a great deal of time. And, if during this process, modeling irregularities are found or fabrication problems arise due to reachability or collision detection issues, then the entire process must start anew.

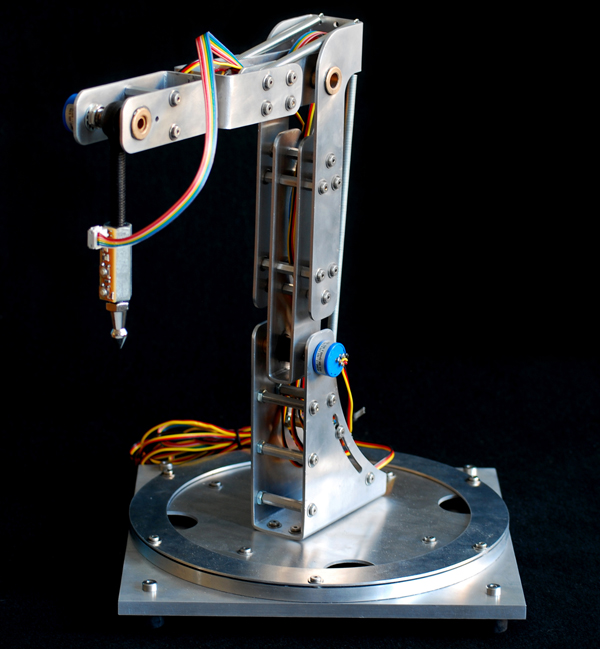

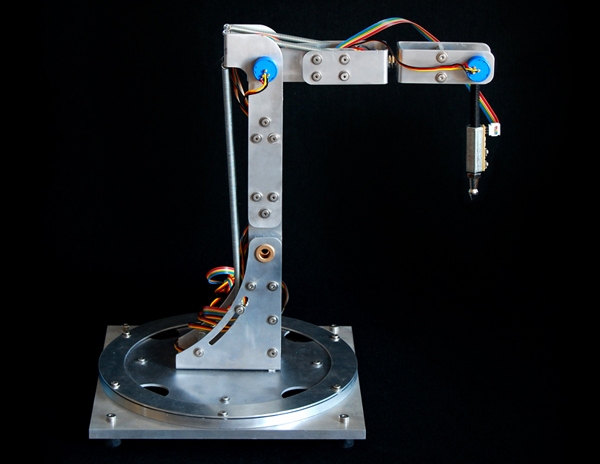

Conceptually, this project started very simply. I began by looking at the joint and axis configurations of the ABB-IRB 140 robot, one of the six axis robots available in the Harvard robotics lab. The design challenge then, was to design a tangible controller around these constraints. By using the same joint and axis configurations, the digitizing arm has a one to one relationship with the larger industrial robot. It is very intuitive. A user immediately grasps the idea that when they move the digitizing arm in a certain way, the robot will respond in kind.

Outside of the development of a new robotic workflow, one of the primary goals of the project was to minimize costs. Given that all of the parts for this project were paid for out of pocket (a student's pocket), creating a low-cost solution was of utmost importance. But, beyond my own personal economic restrictions, I wanted this project to be seen as a do-it-yourself solution - something that could be built in any garage or workbench using easily purchased hardware parts and sensors and a few custom fabricated pieces. The entire controller, shown here, was built for less than $200 dollars. The aluminum body was water jet cut and all of the hardware were pieces that could purchased from local hardware stores or online retailers. All of the sensors, including the five high-precision potentiometers (shown here as the small blue knobs sticking off of the aluminum body) and the two digital sensors on the tool tip were also purchased from online retailers and were chosen because of their affordability.

To create a real-time robotic simulation, data from each of the embedded sensors on the tangible controller are streamed into the computer using a plug-in for Grasshopper that I have also been developing called Firefly. Among other things, Firefly enables the use of real-world data, acquired from various types of sensors or other input devices to explicitly define parametric relationships within a Grasshopper model. In this project, sensor information is used to create a forward kinematic robotic simulation. Forward kinematics describes one type of solution for determining robotic positioning. If given all of the relative angles of each joint and the lengths of each leg; the tool tip (also known as the end effector) can be found by performing a series of matrix transformations on each body in the robotic mechanism. In this case, each of the potentiometers will return a 10-bit number between 0 and 1023. These particular potentiometers were able to rotate up to 340º, so the angle between each joint can be found by simply multiplying the current sensor value by the sensor step size. These angle values are used to perform a matrix transformation on each of the robotic legs, ultimately giving you the precise position of the tool center point. And, once you know the location of the end effector, you can record this data over time to create real-time robotic tool paths.

In addition to the five high-precision potentiometers, the digitizing arm is equipped with a tool tip circuit board with two push button controls. These allow the user to easily record or reset the digitized information on the fly. I also designed and built a customized circuit board (on the left) which processes all of the sensor information and sends a formatted string of information over the serial port to the virtual parametric interface.

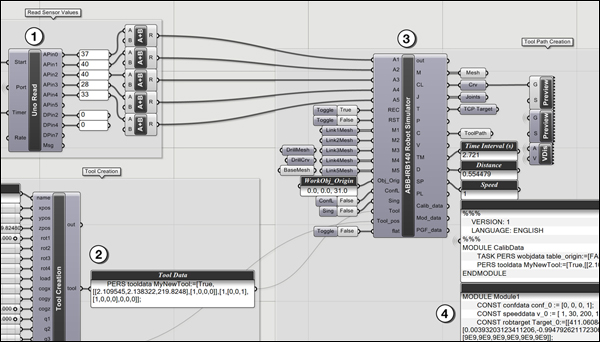

The Grasshopper definition is relatively straight forward. The Firefly Read component parses of the sensor information being sent directly from the microcontroller circuit board. There is a custom component written in VB.NET (seen in item number 2), which creates the necessary tool data. The data from both of these components are fed into another custom component which calculates the forward kinematic solution and outputs the position of each leg, creating a real-time preview of the robot moving in the Rhino viewport. In addition, the robotic simulator also returns all of the RAPID code, or the robotic programming language used by all of the ABB robots, to move the actual robot in the same manner as the forward kinematic preview.

The custom robotic simulation component written inside of Grasshopper outputs all of the necessary RAPID code to control the actual robot. There are two methods by which this can be done. First, all of the digitizing information is recorded and formatted into a composite data type called a robtarget. Each robtarget is defined by its name, absolute position as XYZ coordinates, rotation and orientation of the robot as four quaternion values, and its joint configurations. Each robtarget is given a unique identification each time the solution is recomputed. Then the movement commands are created to tell the robot specifically how to get to each robtarget. Once the program has been written, it can then be saved to a file on disk and uploaded to the robotic controller to be played back. An alternative method is to stream the angle information from the digitizing arm directly to the robot through a network cable. In this method, a program is uploaded to the robot which tells it to sit and wait for any information being sent directly from the Grasshopper definition (which can be seen in the video above).

As of today, there have only been a limited number of test runs using the five-axis robotic controller, however, the initial tests suggest that the proposed direct-to-fabrication process could prove to be a viable alternative to existing robotic workflows. One of the first tests I tried was attaching a custom designed pen tool to the robot to see if the drawing movements of the digitizing arm would match those of the robot. And while spelling your name isn't the most exciting demo, it did show some of the potential available with this process. Because virtually any end effector can be attached to the end of the robot, the design opportunities are endless. And because the tangible controller has a one-to-one relationship with the larger industrial robot, designers immediately understand that their drawing motions will be converted directly into robotic movements, creating a very intuitive interface.

Although there has been considerable progress made in the digital tools used to control robots, I'd like to close by reiterating the fact that there is an identifiable problem in the existing design-to-fabrication process. I would like to propose an improved workflow for robotic fabrication. It is the hope of this project that the physical articulation of embodied input and output through purpose-built tools for fabrication can allow for wider adoption by and new creative opportunities for architects and designers. In turn, I hope this will help re-establish the relationship between designers and the physical fabrication process.

Acknowledgments:

I would like to thank Harvard professors Martin Bechthold and Pangiotis Michalotos as well as Neil Gershenfeld from MIT's Center for Bits and Atoms for their support during the development of this project.